Fold, Spindle, Mutilate

by Richard Goldstein

by Richard Goldstein

FOLD

You could tell something more than springtime was brewing at Columbia by the crowds around the local Chock Full, jumping and gesturing with more than coffee in their veins. You could sense insurrection in the squads of police surrounding the campus like a Navy picket fence. You could see rebellion in the eyes peering from windows where they didn't belong. And you knew it was revolution for sure, from the trash.

Don't underestimate the relationship between litter and liberty at Columbia. Until last Thursday, April 23, the university was a clean dorm, where students paid rent, kept the house rules, and took exams. Then the rebels arrived, in an uneasy coalition of hip, black, and leftist militants. They wanted to make Columbia more like home.

So they ransacked files, shoved furniture around, plastered walls with paint and placards. They scrawled on blackboards and doodled on desks. They raided the administration's offices (the psychological equivalent of robbing your mother's purse) and they claim to have found cigars, sherry, and a dirty book (the psychological equivalent of finding condoms in your father's wallet).

Of course this is a simplification. There were issues involved in the insurrection which paralyzed Columbia this past week. Like the gymnasium in Morningside Park, or the university's ties to the Institute for Defense Analysis. But beyond these specifics, the radicals were trying to capture the imagination of their campus by giving vent to some of its unique frustrations. In short, they had raised the crucial question who was to control Columbia? Four buildings had been "liberated" and occupied by students. The traditional quietism that had been the pride of straight Columbia was giving way to a mood of cautious confrontation. The groovy revolution -- one part dogma to four parts joy -- had been declared.

The rebels totaled upward of 900 during peak hours. They were ensconsed behind sofa-barricades. You entered Fayerweather Hall through a ground floor window. Inside, you saw blackboards filled with "strike bulletins," a kitchen stocked with sandwiches and cauldrons of spaghetti, and a lounge filled with squatters. There was some pot and a little petting in the corridors. But on Friday, the rebellion had the air of a college bar at 2 a.m. In nearby Avery Hall, the top two floors were occupied by architecture students, unaffiliated with SDS, but sympathetic to their demands. They sat at their drawingboards, creating plans for a humanistic city and taping their finished designs across the windows. In Low Library, the strike steering committee and visiting radicals occupied the offices of President Grayson Kirk. On the other side of the campus, the mathematics building was seized late Friday afternoon. The rebels set about festooning walls and making sandwiches. Jimi Hendrix blared from a phonograph. Mao mixed with Montesquieu, "The Wretched of the Earth" mingled with "Valley of the Dolls."

It was a most eclectic uprising, and a most forensic one as well. The debates on and around the campus were endless. Outside Ferris Booth Hall, two policemen in high boots took on a phalanx of SDS supporters. Near Low Library, a leftist in a lumberjack shirt met a rightist in a London Fog. "You've got to keep your people away from here." We don't want any violence," said the leftist. "We have been using the utmost restraint," answered his adversary, "But," insisted the lumberjack shirt, letting his round glasses slide down his nose, "this gentleman here says he was shoved."

In its early stages, at least, it was a convivial affair, a spring carnival without a queen. One student, who named a tree outside Hamilton Hall, had the right idea when he shouted for all to hear: "This is a liberated tree. And I won't come down until my demands have been met."

You could tell something more than springtime was brewing at Columbia by the crowds around the local Chock Full, jumping and gesturing with more than coffee in their veins. You could sense insurrection in the squads of police surrounding the campus like a Navy picket fence. You could see rebellion in the eyes peering from windows where they didn't belong. And you knew it was revolution for sure, from the trash.

Don't underestimate the relationship between litter and liberty at Columbia. Until last Thursday, April 23, the university was a clean dorm, where students paid rent, kept the house rules, and took exams. Then the rebels arrived, in an uneasy coalition of hip, black, and leftist militants. They wanted to make Columbia more like home.

So they ransacked files, shoved furniture around, plastered walls with paint and placards. They scrawled on blackboards and doodled on desks. They raided the administration's offices (the psychological equivalent of robbing your mother's purse) and they claim to have found cigars, sherry, and a dirty book (the psychological equivalent of finding condoms in your father's wallet).

Of course this is a simplification. There were issues involved in the insurrection which paralyzed Columbia this past week. Like the gymnasium in Morningside Park, or the university's ties to the Institute for Defense Analysis. But beyond these specifics, the radicals were trying to capture the imagination of their campus by giving vent to some of its unique frustrations. In short, they had raised the crucial question who was to control Columbia? Four buildings had been "liberated" and occupied by students. The traditional quietism that had been the pride of straight Columbia was giving way to a mood of cautious confrontation. The groovy revolution -- one part dogma to four parts joy -- had been declared.

The rebels totaled upward of 900 during peak hours. They were ensconsed behind sofa-barricades. You entered Fayerweather Hall through a ground floor window. Inside, you saw blackboards filled with "strike bulletins," a kitchen stocked with sandwiches and cauldrons of spaghetti, and a lounge filled with squatters. There was some pot and a little petting in the corridors. But on Friday, the rebellion had the air of a college bar at 2 a.m. In nearby Avery Hall, the top two floors were occupied by architecture students, unaffiliated with SDS, but sympathetic to their demands. They sat at their drawingboards, creating plans for a humanistic city and taping their finished designs across the windows. In Low Library, the strike steering committee and visiting radicals occupied the offices of President Grayson Kirk. On the other side of the campus, the mathematics building was seized late Friday afternoon. The rebels set about festooning walls and making sandwiches. Jimi Hendrix blared from a phonograph. Mao mixed with Montesquieu, "The Wretched of the Earth" mingled with "Valley of the Dolls."

It was a most eclectic uprising, and a most forensic one as well. The debates on and around the campus were endless. Outside Ferris Booth Hall, two policemen in high boots took on a phalanx of SDS supporters. Near Low Library, a leftist in a lumberjack shirt met a rightist in a London Fog. "You've got to keep your people away from here." We don't want any violence," said the leftist. "We have been using the utmost restraint," answered his adversary, "But," insisted the lumberjack shirt, letting his round glasses slide down his nose, "this gentleman here says he was shoved."

In its early stages, at least, it was a convivial affair, a spring carnival without a queen. One student, who named a tree outside Hamilton Hall, had the right idea when he shouted for all to hear: "This is a liberated tree. And I won't come down until my demands have been met."

SPINDLE

Ray Brown stood in the lobby of Hamilton Hall, reading a statement to the press. His followers stood around him, all black and angry. It was 7.30 p.m. Sunday, and the press had been escorted across a barricade of tabletops to stand in the lobby while Brown read his group's demands. By now, there were dozens of committees and coalitions on the campus, and students could choose from five colors of armbands to express their sympathies (red indicated pro-strike militancy, green meant peace with amnesty, pale blue meant an end to demonstrations. White stood for faculty, and black indicated support for force.)

But no faction worried Columbia's administrator's more than the blacks. They had become a political entity at 5 a.m. Wednesday morning when 300 white radicals filed dutifully from Hamilton Hall at the request of the blacks. From that moment, the deserted building became Malcolm X University christened by a sign over the main door. In the lobby were two huge posters of Stokely Carmichael and were allowed to see of Hamilton Hall. The blacks insisted on holding out alone, but by joining the demands of the people in Harlem and the kids in Low, they added immeasurable power to the student coalition. this is easier explained by considering the University's alternatives. To discharge the students from Hamilton meant risking charges of racism, and that meant turning Morningside Park into a rather vulnerable DMZ. To eject only the whites would leave the University with the blame for arbitrarily deciding who was to be clubbed and who spared.

In short, the blacks made the Administration think twice. And Ray Brown knew it. He read his statement to the press, and after it was over, looked down at those of us taking notes and muttered, "Clear the hall." We left.

There was a second factor in the stalemate and its protraction. The issue of university control raised by the radicals had stirred some of the more vocal faculty members into action. They arrived in force on Friday night, when it became known that police were preparing to move. When the administration issued a one hour ultimatum to the strikers early Saturday morning, concerned faculty members formed an ad hoc committee and placed themselves between the students and the police. This line was defied only once -- at 3 a.m. Saturday by two dozen plainclothesmen. A young French instructor was led away with a bleeding head. The administration backed down, again licked its wounds, and waited. It played for time, and allowed the more militant faculty members to expend their energies on futile negotiations. All weekend, the campus radio station, WKCR, broadcast offers for settlement and their eventual rejection. While the Board of Trustees voted to suspend construction of the gymnasium pending further study, they made it clear that their decision was taken at the Mayor's request, and that they were not acceding to any of the striker's demands. Over the weekend, factions multiplied and confusion grew on campus. This too played into the administration's hands. Vice-president David B. Truman blamed the violence, the inconvenience, and the intransigence on the demonstrators. When a line of conservative students formed around Low Library to prevent food from being brought to the protesters, the administration ordered food for the anti-picket line at the school's expense.

Finally, it called the first formal faculty meeting in anyone's memory for Sunday morning. But it made certain that only assistant, associate, and full professors were present. With this qualification, the administration assured itself a resolution that would seem to signify faculty support. Alone and unofficial, the ad hoc committee persisted in its demands, never quite grasping its impotence until late Monday night, when word began to reach the campus that the cops would move.

Ray Brown stood in the lobby of Hamilton Hall, reading a statement to the press. His followers stood around him, all black and angry. It was 7.30 p.m. Sunday, and the press had been escorted across a barricade of tabletops to stand in the lobby while Brown read his group's demands. By now, there were dozens of committees and coalitions on the campus, and students could choose from five colors of armbands to express their sympathies (red indicated pro-strike militancy, green meant peace with amnesty, pale blue meant an end to demonstrations. White stood for faculty, and black indicated support for force.)

But no faction worried Columbia's administrator's more than the blacks. They had become a political entity at 5 a.m. Wednesday morning when 300 white radicals filed dutifully from Hamilton Hall at the request of the blacks. From that moment, the deserted building became Malcolm X University christened by a sign over the main door. In the lobby were two huge posters of Stokely Carmichael and were allowed to see of Hamilton Hall. The blacks insisted on holding out alone, but by joining the demands of the people in Harlem and the kids in Low, they added immeasurable power to the student coalition. this is easier explained by considering the University's alternatives. To discharge the students from Hamilton meant risking charges of racism, and that meant turning Morningside Park into a rather vulnerable DMZ. To eject only the whites would leave the University with the blame for arbitrarily deciding who was to be clubbed and who spared.

In short, the blacks made the Administration think twice. And Ray Brown knew it. He read his statement to the press, and after it was over, looked down at those of us taking notes and muttered, "Clear the hall." We left.

There was a second factor in the stalemate and its protraction. The issue of university control raised by the radicals had stirred some of the more vocal faculty members into action. They arrived in force on Friday night, when it became known that police were preparing to move. When the administration issued a one hour ultimatum to the strikers early Saturday morning, concerned faculty members formed an ad hoc committee and placed themselves between the students and the police. This line was defied only once -- at 3 a.m. Saturday by two dozen plainclothesmen. A young French instructor was led away with a bleeding head. The administration backed down, again licked its wounds, and waited. It played for time, and allowed the more militant faculty members to expend their energies on futile negotiations. All weekend, the campus radio station, WKCR, broadcast offers for settlement and their eventual rejection. While the Board of Trustees voted to suspend construction of the gymnasium pending further study, they made it clear that their decision was taken at the Mayor's request, and that they were not acceding to any of the striker's demands. Over the weekend, factions multiplied and confusion grew on campus. This too played into the administration's hands. Vice-president David B. Truman blamed the violence, the inconvenience, and the intransigence on the demonstrators. When a line of conservative students formed around Low Library to prevent food from being brought to the protesters, the administration ordered food for the anti-picket line at the school's expense.

Finally, it called the first formal faculty meeting in anyone's memory for Sunday morning. But it made certain that only assistant, associate, and full professors were present. With this qualification, the administration assured itself a resolution that would seem to signify faculty support. Alone and unofficial, the ad hoc committee persisted in its demands, never quite grasping its impotence until late Monday night, when word began to reach the campus that the cops would move.

MUTILATE

At 2.30 Tuesday morning 100 policemen poured on campus. The students were warned of the impending assault when the University cut off telephone lines in all occupied buildings. One by one, the liberated houses voted to respond non-violently.

While plainclothesmen were being transported up Amsterdam Avenue in city buses marked "special," the uniformed force moved first on Hamilton Hall. The students there marched quietly from their sanctuary after police reached them via the school's tunnels. There were no visible injuries as they boarded a bus to be led away, and this tranquil surrender spurred rumors that a mutual cooperation pact of sorts had been negotiated between police and black demonstrators.

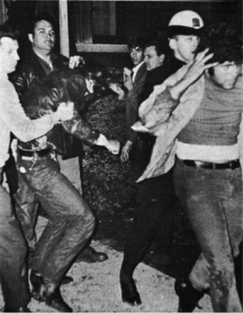

Things were certainly different in the other buildings. Outside Low Memorial Library, police rushed a crowd of students, clubbing some with blackjacks and pulling others by the hair.

"There's gonna be a lot of bald heads tonight," one student said.

Uniformed police were soon joined by plainclothesmen, identifiable only by the tiny orange buttons in their lapels. Many were dressed to resemble students. Some carried books, others wore Coptic crosses around their necks. You couldn't tell, until they started to operate, that they were cops.

At Mathematics Hall, police broke through the ground floor window and smashed the barricade at the front door. Students who agreed to surrender peacefully were allowed to do so with little interference. They walked between rows of police, through Low Plaza, and into vans that lined College Walk. In the glare of the floodlights which normally light that part of the campus at night, it looked like a bizarre pogrom. Platoons of prisoners appeared, waving their hands in victory signs and singing "We Shall Overcome." A large crowd of sympathizers were separated from the prisoners by a line of police, but their shouts of "Kirk Must Go" rocked the campus. Police estimated that at least 628 students were jailed, 100 of them women. Officials at nearby Saint Luke's Hospital reported that 74 students were admitted for treatment. This figure did not include those who were more seriously injured, since these were removed to Knickerbocker Hospital by ambulance. Three faculty members were reportedly hurt.

Many of the injuries occurred among those students who refused to leave the buildings. Police entered Fayerweather and Mathematics Halls and dragged limp students down the stairs. The sound of thumping bodies was plainly audible at times (demonstrators had waxed the floors to hamper police). Many emerged in masks of vaseline applied to ward off the effects of Mace. Police made no attempt to gas the demonstrators. But some of those who had barricaded themselves in classrooms reported that teams of police freely pummeled them. A line heard by more than one protester, as the police moved to dislodge groups linking arms, was "Up against the wall, motherfuckers."

There was no example of incredible police brutality visible at Columbia on Tuesday morning. It was all credible brutality. Plainclothesmen occasionally kicked limp demonstrators, often with quick jabs in the stomach. I saw students pulled away by the hair, scraped against broken glass, and when they proved difficult to carry, beaten repeatedly. Outside Mathematics Hall, a male student in a leather jacket was thrown to the ground when he refused to walk and beaten by a half dozen officers while plainclothesmen kept reporters at a distance. When he was finally led away, his jacket and shirt had been ripped from his back.

The lounge at Philosophy Hall, which had been used by the ad hoc faculty committee as an informal senate, became a field hospital. Badly injured students lay on beds and sofas while stunned faculty members passed coffee, took statements, and supplied bandages. The most violent incidents had occurred nearby, in Fayerweather Hall, where many students who refused to leave were dragged away bleeding from the face and scalp. Medical aides who had moved the injured to a nearby lawn trailed the police searching for bleeding heads. "Don't take him, he's bleeding," you heard them shout. Or: "Pick her up, stop dragging her."

The cries of the injured echoed off the surrounding buildings and the small quad looked like a battlefield. Those who were awaiting arrest formed an impromptu line. Facing the police, they sang a new verse to an old song:

"Harlem shall awake,

Harlem shall awake,

Harlem shall awake someday..."

Though two of Mayor Lindsay's top aides, Sid Davidoff and Barry Gottehrer, had been present throughout the night, neither was seen to make any restraining move toward the police. Commissioner Leary congratulated his men. And University President Grayson Kirk regretted that even such minimal violence was necessary.

By dawn, the rebellion had ended. Police cleared the campus of remaining protesters by charging, nightsticks swinging, into a large crowd which had gathered around the sundial. Now, the cops stood in a vast line across Low Library Plaza. Their boots and helmets gleamed in the floodlights. Later in the morning, a reporter from WKCR would encounter some of these arresting officers at the Tombs, where the prisoners were being held. He would hear them singing "We Shall Overcome," and shouting, "victory."

At present, it is difficult to measure the immediate effects Tuesday's police intervention will have on the university. Most students are too stunned to consider the future. On Tuesday morning they stood in small knots along Broadway, stepping around the horse manure and watching the remaining policemen leave. Their campus lay scarred and littered. Walks were inundated with newspapers, beer cans, broken glass, blankets, and even discarded shoes. Flower-beds had been trampled and hedges mowed down in some places. Windows were broken in at least three buildings and whole classrooms had been demolished.

It would take a while to make Columbia beautiful again. That, most students agreed. And some insisted that it would take much longer before the university would seem a plausible place to teach or study in again. The revolution had begun and ended in trash, and that litter would persist to haunt Columbia, and especially its president, Grayson Kirk.

At 2.30 Tuesday morning 100 policemen poured on campus. The students were warned of the impending assault when the University cut off telephone lines in all occupied buildings. One by one, the liberated houses voted to respond non-violently.

While plainclothesmen were being transported up Amsterdam Avenue in city buses marked "special," the uniformed force moved first on Hamilton Hall. The students there marched quietly from their sanctuary after police reached them via the school's tunnels. There were no visible injuries as they boarded a bus to be led away, and this tranquil surrender spurred rumors that a mutual cooperation pact of sorts had been negotiated between police and black demonstrators.

Things were certainly different in the other buildings. Outside Low Memorial Library, police rushed a crowd of students, clubbing some with blackjacks and pulling others by the hair.

"There's gonna be a lot of bald heads tonight," one student said.

Uniformed police were soon joined by plainclothesmen, identifiable only by the tiny orange buttons in their lapels. Many were dressed to resemble students. Some carried books, others wore Coptic crosses around their necks. You couldn't tell, until they started to operate, that they were cops.

At Mathematics Hall, police broke through the ground floor window and smashed the barricade at the front door. Students who agreed to surrender peacefully were allowed to do so with little interference. They walked between rows of police, through Low Plaza, and into vans that lined College Walk. In the glare of the floodlights which normally light that part of the campus at night, it looked like a bizarre pogrom. Platoons of prisoners appeared, waving their hands in victory signs and singing "We Shall Overcome." A large crowd of sympathizers were separated from the prisoners by a line of police, but their shouts of "Kirk Must Go" rocked the campus. Police estimated that at least 628 students were jailed, 100 of them women. Officials at nearby Saint Luke's Hospital reported that 74 students were admitted for treatment. This figure did not include those who were more seriously injured, since these were removed to Knickerbocker Hospital by ambulance. Three faculty members were reportedly hurt.

Many of the injuries occurred among those students who refused to leave the buildings. Police entered Fayerweather and Mathematics Halls and dragged limp students down the stairs. The sound of thumping bodies was plainly audible at times (demonstrators had waxed the floors to hamper police). Many emerged in masks of vaseline applied to ward off the effects of Mace. Police made no attempt to gas the demonstrators. But some of those who had barricaded themselves in classrooms reported that teams of police freely pummeled them. A line heard by more than one protester, as the police moved to dislodge groups linking arms, was "Up against the wall, motherfuckers."

There was no example of incredible police brutality visible at Columbia on Tuesday morning. It was all credible brutality. Plainclothesmen occasionally kicked limp demonstrators, often with quick jabs in the stomach. I saw students pulled away by the hair, scraped against broken glass, and when they proved difficult to carry, beaten repeatedly. Outside Mathematics Hall, a male student in a leather jacket was thrown to the ground when he refused to walk and beaten by a half dozen officers while plainclothesmen kept reporters at a distance. When he was finally led away, his jacket and shirt had been ripped from his back.

The lounge at Philosophy Hall, which had been used by the ad hoc faculty committee as an informal senate, became a field hospital. Badly injured students lay on beds and sofas while stunned faculty members passed coffee, took statements, and supplied bandages. The most violent incidents had occurred nearby, in Fayerweather Hall, where many students who refused to leave were dragged away bleeding from the face and scalp. Medical aides who had moved the injured to a nearby lawn trailed the police searching for bleeding heads. "Don't take him, he's bleeding," you heard them shout. Or: "Pick her up, stop dragging her."

The cries of the injured echoed off the surrounding buildings and the small quad looked like a battlefield. Those who were awaiting arrest formed an impromptu line. Facing the police, they sang a new verse to an old song:

"Harlem shall awake,

Harlem shall awake,

Harlem shall awake someday..."

Though two of Mayor Lindsay's top aides, Sid Davidoff and Barry Gottehrer, had been present throughout the night, neither was seen to make any restraining move toward the police. Commissioner Leary congratulated his men. And University President Grayson Kirk regretted that even such minimal violence was necessary.

By dawn, the rebellion had ended. Police cleared the campus of remaining protesters by charging, nightsticks swinging, into a large crowd which had gathered around the sundial. Now, the cops stood in a vast line across Low Library Plaza. Their boots and helmets gleamed in the floodlights. Later in the morning, a reporter from WKCR would encounter some of these arresting officers at the Tombs, where the prisoners were being held. He would hear them singing "We Shall Overcome," and shouting, "victory."

At present, it is difficult to measure the immediate effects Tuesday's police intervention will have on the university. Most students are too stunned to consider the future. On Tuesday morning they stood in small knots along Broadway, stepping around the horse manure and watching the remaining policemen leave. Their campus lay scarred and littered. Walks were inundated with newspapers, beer cans, broken glass, blankets, and even discarded shoes. Flower-beds had been trampled and hedges mowed down in some places. Windows were broken in at least three buildings and whole classrooms had been demolished.

It would take a while to make Columbia beautiful again. That, most students agreed. And some insisted that it would take much longer before the university would seem a plausible place to teach or study in again. The revolution had begun and ended in trash, and that litter would persist to haunt Columbia, and especially its president, Grayson Kirk.